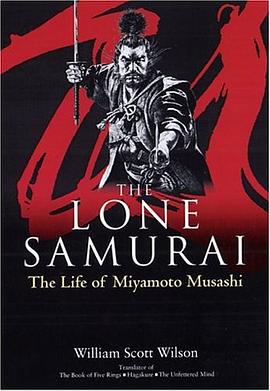

The Lone Samurai pdf epub mobi txt 电子书 下载 2026

- 宫本武藏

- samurai

- japan

- martial arts

- history

- adventure

- fantasy

- warrior

- culture

- discipline

- solitude

具体描述

The Lone Samurai is a landmark biography of Miyamoto Musashi, the legendary Japanese figure known throughout the world as a master swordsman, spiritual seeker, and author of The Book of Five Rings. With a compassionate yet critical eye, William Scott Wilson delves into the workings of

Musashi's mind as the iconoclastic samurai wrestled with philosophical and spiritual ideas that are as relevant today as they were in his times. Musashi found peace and spiritual reward in seeking to perfect his chosen Way, and came to realize that perfecting a single Way, no matter the path, could

lead to fulfillment. The Lone Samurai is far more than a vivid account of a fascinating slice of feudal Japan. It is the story of one man's quest for answers, perfection, and access to the Way.

By age thirteen, Miyamoto Musashi had killed his opponent in what would become the first of many celebrated swordfights. By thirty, he had fought more than sixty matches, losing none. He would live another thirty years but kill no one else. He continued to engage in swordfights but now began to show

his skill simply by thwarting his opponents' every attack until they acknowledged Musashi's all-encompassing ability. At the same time, the master swordsman began to expand his horizons, exploring Zen Buddhism and its related arts, particularly ink painting, in a search for a truer Way.

Musashi was a legend in his own time. As a swordsman, he preferred the wooden sword and in later years almost never fought with a real weapon. He outfoxed his opponents or turned their own strength against them. At the height of his powers, he began to evolve artistically and spiritually, becoming

one of the country's most highly regarded ink painters and calligraphers, while deepening his practice of Zen Buddhism. He funneled his hard-earned insights about the warrior arts into his spiritual goals. Ever the solitary wanderer, Musashi shunned power, riches, and the comforts of a home or fixed

position with a feudal lord in favor of a constant search for truth, perfection, and a better Way. Eventually, he came to the realization that perfection in one art, whether peaceful or robust, could offer entry to a deeper, spiritual understanding. His philosophy, along with his warrior strategies,

is distilled in his renowned work, The Book of Five Rings, written near the end of his life.

Musashi remains a source of fascination for the Japanese, as well as for those of us in the West who have more recently discovered the ideals of the samurai and Zen Buddhism. The Lone Samurai is the first biography ever to appear in English of this richly layered, complex seventeenth-century

swordsman and seeker, whose legacy has lived far beyond his own time and place.

---------------------------------------------------------------- INTERVIEW WITH WILLIAM SCOTT WILSON ABOUT BUSHIDO

Q.: What is Bushido?

A.: Bushido might be explained in part by the etymology of the Chinese characters used for the word. Bu comes from two radicals meanings "stop" and "spear." So even though the word now means "martial" or "military affair," it has the sense of stopping aggression. Shi can mean "samurai," but also

means "gentleman" or "scholar." Looking at the character, you can see a man with broad shoulders but with his feet squarely on the ground. Do, with the radicals of head and motion, originally depicted a thoughtful way of action. It now means a path, street or way. With this in mind, we can

understand Bushido as a Way of life, both ethical and martial, with self-discipline as a fundamental tenet. Self-discipline requires the warrior at once to consider his place in society and the ethics involved, and to forge himself in the martial arts. Both should eventually lead him to understand

that his fundamental opponents are his own ignorance and passions.

Q.: How did the code develop and how did it influence Japanese society?

A.: The warrior class began to develop as a recognizable entity around the 11th and 12th centuries. The leaders of this class were often descended from the nobility, and so were men of education and breeding. I would say that the code developed when the leaders of the warrior class began to reflect

on their position in society and what it meant to be a warrior. They first began to write these thoughts down as yuigon, last words to their descendents, or as kabegaki, literally "wall writings," maxims posted to all their samurai. Samurai itself is an interesting word, coming from the classical

saburau, "to serve." So when we understand that a samurai is "one who serves," we see that the implications go much farther than simply being a soldier or fighter.

Also, it is important to understand that Confucian scholars had always reflected on what it meant to be true gentleman, and they concluded that such a man would be capable of both the martial and literary. The Japanese inherited this system of thought early on, so certain ideals were already

implicitly accepted.

The warrior class ruled the country for about 650 years, and their influence-political, philosophical and even artistic-had a long time to percolate throughout Japanese society.

Q.: The Samurai were very much renaissance men - they were interested in the arts, tea ceremony, religion, as well as the martial arts. What role did these interests play in the development of Bushido? How did the martial arts fit in?

A.: This question goes back to the Confucian ideal of balance that Japanese inherited, probably from the 7th century or so. The word used by both to express this concept, for the "gentleman" by the Chinese and the warrior by Japanese, is (hin), pronounced uruwashii in Japanese, meaning both

"balanced" and "beautiful." The character itself is a combination of "literature" (bun) and "martial" (bu). The study of arts like Tea ceremony, calligraphy, the study of poetry or literature, and of course the martial arts of swordsmanship or archery, broadened a man's perspective and understanding

of the world and, as mentioned above, provided him with a vehicle for self-discipline. The martial arts naturally were included in the duties of a samurai, but this did not make them any less instructive in becoming a full human being.

Q.: What was sword fighting like? Was the swordplay different for different samurai?

A.: There were literally hundreds of schools of samurai swordsmanship by the 1800's and, as previously mentioned, each school emphasized differing styles and approaches. Some would have the student to jump and leap, others to keep his feel solidly on the ground; some would emphasize different ways

of holding the sword, others one method only. One school stated that technical swordsmanship took second place to sitting meditation. Historically speaking, there were periods when much of the swordfighting was done on horseback, and others when it was done mostly on foot. Also, as the shape and

length of the sword varied through different epochs, so did styles of fighting. Then I suppose that a fight between men who were resolved to die would be quite different from a fight between men who were not interested in getting hurt.

Q.: How is the code reflected in Japanese society today?

A.: When I first came to live in Japan in the 60's, I was impressed how totally dedicated and loyal people were to the companies where they were employed. When I eventually understood the words samurai and saburau, it started to make sense. While these men (women would usually not stay long with a

company, giving up work for marriage) did not carry swords of course, they seemed to embody that old samurai sense of service, duty, loyalty and even pride. This may sound strange in our own "me first" culture, but it impressed me that the company had sort of taken the place of a feudal lord, and

that the stipend of the samurai had become the salary of the white-collar worker.M

That is on the societal level. On an individual level, I have often felt that Japanese have a strong resolution, perhaps from this cultural background of Bushido, to go through problems rather than around them. Persistence and patience developed from self-discipline?

作者简介

目录信息

读后感

评分

评分

评分

评分

用户评价

我必须承认,这本书的语言风格美得令人窒息,简直像是从古典诗歌的典籍中直接汲取了养分,然后用现代的敏感性进行了重塑。每一个句子都经过了精心的雕琢,词汇的选择极具画面感和触感。你仿佛能闻到文字中描绘的湿润泥土的气息,感受到拂过皮肤的微凉的晨风。然而,这种极致的美感也带来了阅读上的巨大阻力。作者似乎沉迷于冗长且层层嵌套的从句,使得一个简单的意象需要花费数行文字才能完整呈现。初读时,我经常需要停下来,一遍又一遍地咀嚼那些复杂的修饰语和排比句,生怕错过任何一个微妙的情绪波动或意境的转折。这导致阅读速度变得极其缓慢,与情节的快速发展形成了鲜明的对比——情节在背后默默地向前推进,而我却被困在了对当前这一句华丽辞藻的欣赏和理解之中。对于追求直接叙事和高效信息传递的读者来说,这本书可能显得过于矫揉造作,但对于那些珍视语言本身音乐性和雕塑感的人而言,它无疑是一场盛宴,尽管这场宴席需要极大的耐心才能享用完毕。

评分从主题的探讨深度来看,这部书无疑是深刻的,它触及了诸如记忆的不可靠性、身份的流动性以及集体无意识的巨大惯性等一系列宏大议题。作者毫不避讳地将一些非常尖锐的社会批判隐藏在看似奇幻的外壳之下,挑战了读者对既有道德观和历史叙事的固有认知。然而,这种深刻性却常常被一种过度的象征主义所笼罩,使得其清晰的批判意图变得模糊不清。书中充斥着大量的重复符号——一只断掉的翅膀、一面破碎的镜子、永不熄灭的灯火——它们无疑承载了重要的寓意,但由于它们出现的频率过高且缺乏明确的上下文指引,它们的作用最终退化成了某种装饰性的元素,而非推动主题理解的有效工具。我渴望作者能给予读者更明确的“锚点”,哪怕只是一个短暂的、清晰的道德困境,来帮助我更好地理解作者试图传达的复杂哲学信息,而不是仅仅通过反复堆砌晦涩的意象来制造“深度”的假象。

评分这本书在世界构建上的雄心壮志令人印象深刻,它描绘了一个细节丰富到令人发指的架空社会体系。从其独特的社会阶层划分,到渗透到日常生活的仪式和禁忌,作者似乎花费了数年时间来设计这个平行宇宙的每一个齿轮。然而,这种详尽的铺陈在某种程度上反而削弱了故事的张力。我可以清晰地‘看到’这个世界的运作原理,理解不同派系之间的权力斗争是如何被那些复杂的律法和古老的契约所制约的。但问题在于,人物似乎成了这个宏大机制的附属品,他们的个人命运和情感纠葛,最终都被纳入到对‘系统’运行的描述之中。我读到他们为了维护某个古老的规定而做出巨大牺牲时,与其说我感到悲伤,不如说我产生了一种近乎工程师般的敬佩,赞叹作者将这个复杂模型搭建得如此精密。这使得人物的代入感大大降低,读者更像是一个外部的、略带疏离感的社会学家,在观察一个运行良好的、但却缺乏人情味的精密仪器。

评分这部作品的叙事结构简直是一场思维的迷宫,作者似乎故意挑战读者的认知边界。它不是那种能让你轻松“看”完的书,更像是一场需要全神贯注去“解码”的旅程。情节的推进充满了令人意想不到的断裂和跳跃,仿佛每一章都是一个独立存在的艺术品,它们之间靠着某种晦涩的象征意义或重复出现的主题线索勉强维系在一起。我花了大量时间去回溯之前读到的只言片语,试图拼凑出一个完整的世界观,但每一次自认为抓住了核心,作者又立刻用一个全新的、更具颠覆性的视角将它瓦解。特别是对时间概念的处理,模糊了过去、现在和潜在未来的界限,让你不禁怀疑自己所依赖的现实基础是否牢靠。那些人物的对话,与其说是信息交流,不如说是哲学思辨的片段,充满了对存在、虚无以及人类局限性的拷问。虽然阅读过程充满了挫败感,但那种智力上的高强度挑战感是极其罕见的,它强迫你跳出舒适区,用一种前所未有的方式去审视叙事本身的力量。它更像是一本需要反复研读、在空白处做满笔记的学术文本,而不是用来消遣的小说。

评分这部作品的节奏感极其不稳定,如同心脏病人的心电图,忽快忽慢,让人无所适从。书的开篇部分,节奏缓慢得令人绝望,大量的内心独白和环境烘托,几乎没有实质性的动作发生,仿佛在为一场即将到来的风暴积蓄能量。我一度怀疑自己是否拿错了一本散文集。然而,当故事终于进入到中期的高潮时,所有的铺垫瞬间爆发,情节以一种令人眩晕的速度向前推进,关键的转折和冲突密集地在三到四章内被压缩完成。这种突如其来的加速感让读者几乎没有时间去消化刚刚发生的一切,更别提去感受人物的情绪反应。等我试图放慢速度,仔细品味那些剧烈的冲突时,故事已经跳跃到了另一个时间点或场景。这种极端的节奏差异,使得情感体验变得非常破碎,读者很难持续地沉浸在任何一个特定的情绪状态中。它更像是由一系列精心设计的、但彼此之间衔接得有些生硬的短片剪辑而成,而非一个流畅的整体叙事。

评分 评分 评分 评分 评分相关图书

本站所有内容均为互联网搜索引擎提供的公开搜索信息,本站不存储任何数据与内容,任何内容与数据均与本站无关,如有需要请联系相关搜索引擎包括但不限于百度,google,bing,sogou 等

© 2026 book.wenda123.org All Rights Reserved. 图书目录大全 版权所有