GENERAL INTRODUCTION

UNCOVERING THE STRUCTURE OF THE TEACHING

Though his teaching is highly systematic, there is no single text that can be ascribed to the Buddha in which he defines the architecture of the Dhamma, the scaffolding upon which he has framed his specific expressions of the doctrine. In the course of his long ministry, the Buddha taught in different ways as determined by occasion and circumstances. Sometimes he would enunciate invariable principles that stand at the heart of the teaching. Sometimes he would adapt the teaching to accord with the proclivities and aptitudes of the people who came to him for guidance. Sometimes he would adjust his exposition to fit a situation that required a particular response. But throughout the collections of texts that have come down to us as authorized “Word of the Buddha,” we do not find a single sutta, a single discourse, in which the Buddha has drawn together all the elements of his teaching and assigned them to their appropriate place within some comprehensive system.

While in a literate culture in which systematic thought is highly prized the lack of such a text with a unifying function might be viewed as a defect, in an entirely oral culture—as was the culture in which the Buddha lived and moved—the lack of a descriptive key to the Dhamma would hardly be considered significant. Within this culture neither teacher nor student aimed at conceptual completeness. The teacher did not intend to present a complete system of ideas; his pupils did not aspire to learn a complete system of ideas. The aim that united them in the process of learning—the process of transmission—was that of practical training, self-transformation, the realization of truth, and unshakable liberation of the mind. This does not mean, however, that the teaching was always expediently adapted to the situation at hand. At times the Buddha would present more panoramic views of the Dhamma that united many components of the path in a graded or Wide-ranging structure. But though there are several discourses that exhibit a broad scope, they still do not embrace all elements of the Dhamma in one overarching scheme.

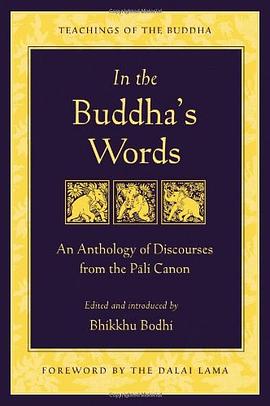

The purpose of the present book is to develop and exemplify such a scheme. I here attempt to provide a comprehensive picture of the Buddha’s teaching that incorporates a wide variety of suttas into an organic structure. This structure, I hope, will bring to light the intentional pattern underlying the Buddha’s formulation of the Dhamma and thus provide the reader with guidelines for understanding Early Buddhism as a whole. I have selected the suttas almost entirely from the four major collections or Nikayas of the Päli Canon, though I have also included a few texts from the Udana and Itivuttaka, two small books of the fifth collection, the Khuddaka Nikaya. Each chapter opens with its own introduction, in which I explain the basic concepts of Early Buddhism that the texts exemplify and show how the texts give expression to these ideas.

I will briefly supply background information about the Nikayas later in this introduction. First, however, I want to outline the scheme that I have devised to organize the suttas. Although my particular use of this scheme may be original, it is not sheer innovation but is based upon a threefold distinction that the Päli commentaries make among the types of benefits to which the practice of the Dhamma leads: (1) welfare and happiness visible in this present life; (2) welfare and happiness pertaining to future lives; and (3) the ultimate good, Nibbãna (Skt: nirvana).

Three preliminary chapters are designed to lead up to those that embody this threefold scheme. Chapter I is a survey of the human condition as it is apart from the appearance of a Buddha in the world. Perhaps this was the way human life appeared to the Bodhisatta—the future Buddha—as he dwelled in the Tusita heaven gazing down upon the earth, awaiting the appropriate occasion to descend and take his final birth. We behold a world in which human beings are driven helplessly toward old age and death; in which they are spun around by circumstances so that they are oppressed by bodily pain, cast down by failure and misfortune, made anxious and fearful by change and deterioration. It is a world in which people aspire to live in harmony, but in which their untamed emotions repeatedly compel them, against their better judgment, to lock horns in conflicts that escalate into violence and wholesale devastation. Finally, taking the broadest view of all, it is a world in which sentient beings are propelled forward, by their own ignorance and craving, from one life to the next, wandering blindly through the cycle of rebirths called samsãra.

Chapter II gives an account of the Buddha’s descent into this world. He comes as the “one person” who appears out of compassion for the world, whose arising in the world is “the manifestation of great light.” We follow the story of his conception and birth, of his renunciation and quest for enlightenment, of his realization of the Dhamma, and of his decision to teach. The chapter ends with his first discourse to the five monks, his first disciples, in the Deer Park near Bärãnasi.

Chapter III is intended to sketch the special features of the Buddha’s teaching, and by implication, the attitude with which a prospective student should approach the teaching. The texts tell us that the Dhanima is not a secret or esoteric teaching but one which “shines when taught openly.” It does not demand blind faith in authoritarian scriptures, in divine revelations, or infallible dogmas, but invites investigation and appeals to personal experience as the ultimate criterion for determining its validity. The teaching is concerned with the arising and cessation of suffering, which can be observed in one’s own experience. It does not set up even the Buddha as an unimpeachable authority but invites us to examine him to determine whether he fully deserves our trust and confidence. Finally, it offers a step-by-step procedure whereby we can put the teaching to the test, and by doing so realize the ultimate truth for ourselves.

With chapter IV, we come to texts dealing with the first of the three types of benefit the Buddha’s teaching is intended to bring. This is called “the welfare and happiness visible in this present life” (ditthadhamma-hitasukha), the happiness that comes from following ethical norms in one’s family relationships, livelyhood, and communal activities. Although Early Buddhism is often depicted as a radical discipline of renunciation directed to a transcendental goal, the Nikayas reveal the Buddha to have been a compassionate and pragmatic teacher who was intent on promoting a social order in which people can live together peacefully and harmoniously in accordance with ethical guidelines. This aspect of Early Buddhism is evident in the Buddha’s teachings on the duties of children to their parents, on the mutual obligations of husbands and wives, on right livelihood, on the duties of the ruler toward his subjects, and on the principles of communal harmony and respect.

The second type of benefit to which the Buddha’s teaching leads is the subject of chapter V. called the welfare and happiness pertaining to the future life (samparayika-hitasukha). This is the happiness achieved by obtaining a fortunate rebirth and success in future lives through one’s accumulation of merit. The term “merit” (puñna) refers to wholesome kamma (Skt: karma) considered in terms of its capacity to produce favorable results within the round of rebirths. I begin this chapter with a selection of texts on the teaching of kamma and rebirth. This leads us to general texts on the idea of merit, followed by selections on the three principal “bases of merit” recognized in the Buddha’s discourses: giving (dana), moral discipline (sda), and meditation (bhavana). Since meditation figures prominently in the third type of benefit, the kind of meditation emphasized here, as a basis for merit, is that productive of the most abundant mundane fruits, the four “divine abodes” (brahmavihara), particularly the development of loving-kindness.

Chapter VI is transitional, intended to prepare the way for the chapters to follow. While demonstrating that the practice of his teaching does indeed conduce to happiness and good fortune within the bounds of mundane life, in order to lead people beyond these bounds, the Buddha exposes the danger and inadequacy in all conditioned existence. He shows the defects in sensual pleasures, the shortcomings of material success, the inevitability of death, and the impermanence of all conditioned realms of being. To arouse in his disciples an aspiration for the ultimate good, Nibbana, the Buddha again and again underscores the perils of sarnsära. Thus this chapter comes to a climax with two dramatic texts that dwell on the misery of bondage to the round of repeated birth and death.

The following four chapters are devoted to the third benefit that the Buddha’s teaching is intended to bring: the ultimate good (paramattha), the attainment of Nibbana. The first of these, chapter VII, gives a general overview of the path to liberation, which is treated analytically through definitions of the factors of the Noble Eightfold Path and dynamically through an account of the training of the monk. A long sutta on the graduated path surveys the monastic training from the monk’s initial entry upon the life of renunciation to his attainment of arahantship, the final goal.

Chapter VIII focuses upon the taming of the mind, the major emphasis in the monastic training. I here present texts that discuss the obstacles to mental development, the means of overcoming these obstacles, different methods of meditation, and the states to be attained when the obstacles are overcome and the disciple gains mastery over the mind. In this chapter I introduce the distinction between samatha and vipassana, serenity and insight, the one leading to samadhi or concentration, the other to panna or wisdom. However, I include texts that treat insight only in terms of the methods used to generate it, not in terms of its actual contents.

Chapter IX, titled “Shining the Light of Wisdom,” deals with the content of insight. For Early Buddhism, and indeed for almost all schools of Buddhism, insight or wisdom is the principal instrument of liberation. Thus in this chapter I focus on the Buddha’s teachings about such topics pivotal to the development of wisdom as right view, the five aggregates, the six sense bases, the eighteen elements, dependent origination, and the Four Noble Truths. This chapter ends with a selection of texts on Nibbäna, the ultimate goal of wisdom.

The final goal is not achieved abruptly but by passing through a series of stages that transforms an individual from a worldling into an arahant, a liberated one. Thus chapter X, “The Planes of Realization,” offers a selection of texts on the main stages along the way. I first present the series of stages as a progressive sequence; then I return to the starting point and examine three major milestones within this progression: stream-entry, the stage of nonreturner, and arahantship. I conclude with a selection of suttas on the Buddha, the foremost among the arahants, here spoken of under the epithet he used most often when referring to himself, the Tathagata.

具體描述

讀後感

評分

評分

評分

評分

用戶評價

經文節選+分析論文,聞思修到證果的編譯順序,脈絡清晰查閱方便。Nikaya/Agama都沒讀透簡直不好意思說自己在學大乘。基礎要牢靠,不要眼高手低…

评分經文節選+分析論文,聞思修到證果的編譯順序,脈絡清晰查閱方便。Nikaya/Agama都沒讀透簡直不好意思說自己在學大乘。基礎要牢靠,不要眼高手低…

评分巴利經藏詮釋 菩提長老 Bhikkhu Bodhi

评分經文節選+分析論文,聞思修到證果的編譯順序,脈絡清晰查閱方便。Nikaya/Agama都沒讀透簡直不好意思說自己在學大乘。基礎要牢靠,不要眼高手低…

评分巴利經藏詮釋 菩提長老 Bhikkhu Bodhi

相關圖書

本站所有內容均為互聯網搜索引擎提供的公開搜索信息,本站不存儲任何數據與內容,任何內容與數據均與本站無關,如有需要請聯繫相關搜索引擎包括但不限於百度,google,bing,sogou 等

© 2025 qciss.net All Rights Reserved. 小哈圖書下載中心 版权所有