具体描述

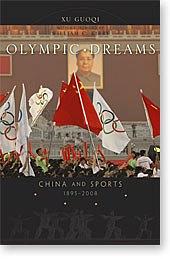

Already the world has seen the political, economic, and cultural significance of hosting the 2008 Olympics in Beijing - in policies instituted and altered, positions softened, projects undertaken. But will the Olympics make a lasting difference? This book approaches questions about the nature and future of China through the lens of sports - particularly as sports finds its utmost international expression in the Olympics.Drawing on newly available archival sources to analyze a hundred-year perspective on sports in China, "Olympic Dreams" explores why the country became obsessed with Western sports at the turn of the twentieth century, and how it relates to China's search for a national and international identity. Through case studies of ping-pong diplomacy and the Chinese handling of various sporting events, the book offers unexpected details and unusual insight into the patterns and processes of China's foreign policymaking - insights that will help readers understand China's interactions with the rest of the world.Among the questions Xu Guoqi brings to the fore are: Why did Mao Zedong choose competitive ping-pong to manipulate world politics? How did the two-China issue nearly kill the 1976 Montreal Olympic Games? And why do the 2008 Olympics present Beijing with unprecedented dangers and opportunities? In exploring these questions, Xu brilliantly articulates a fresh and surprising perspective on China as an international sport superpower as well as a new "sick man of East Asia." In "Olympic Dreams", he presents an eloquent argument that in the deeply unsettled China of today, sport, as a focus of popular interest, has the capacity to bring about major social changes.

作者简介

A review from Edward Cody

The Chinese government has said over and over in the last few months that the Beijing Olympics should not be politicized. The uproar over Tibet has no place in the Games, officials insist. Nor do humanitarian concerns over Sudan's Darfur region belong in the Olympic spotlight. As for human rights in China itself, well, that's an internal matter.

Yet, politics have long been at the heart of China's relations with the modern Olympic movement, as Xu Guoqi, an associate professor at Kalamazoo College, shows in his illuminating history, Olympic Dreams. The first time China participated in the Games, in 1932 at Los Angeles, the goal was to prevent Japan from scoring a propaganda coup. Japanese occupation authorities had planned to dispatch a stocky Chinese sprinter named Liu Changchun to represent the Manchukuo republic, the puppet state Japan had set up in Manchuria and Mongolia. To foil that plan, China's Nationalist government hurriedly scraped together some money and sent Liu as a one-man Chinese delegation. He fared poorly as a sprinter but held high the Chinese flag.

Later on, Mao Zedong saw sports victories as a way to prove the superiority of the socialist way. On advice from the U.S.S.R., China cultivated national teams. But during the first two decades of Communist rule, China kept its athletes out of the Olympics to protest Taiwan's participation. (More recently, both China and Taiwan have sent teams under artful compromises over the island's name.)

When Mao decided the time had come to make friends in the West, he also found sports a handy tool for that purpose. Mao and President Nixon had been exchanging secret messages through intermediaries for months before the Chinese sent a team to the World Table Tennis Championship in Japan in April 1971. As Xu relates, Zhou En-lai, who was in charge of foreign relations, issued detailed instructions to the Chinese players on what to do if they met Americans. "The Chinese were not permitted to exchange team flags," for example, but they "could shake hands," Xu notes. When American player Glenn Cowan jumped on a Chinese bus to greet Chinese star Zhuang Zedong, Zhuang was ready with a silk painting to present as a gift. Mao then gave the order for the Chinese players to invite the U.S. team to China; by the end of the month, the Americans had alighted in Beijing. "The small ping-pong ball, worth only about 25 cents, played a unique and significant role . . . in transforming Sino-U.S. relations," Xu concludes.

Even before Mao, sports had played an eminently political role in China. Chinese nationalists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries saw athletics as a way to create vigorous men who could wage war and change the country's reputation as the "sick man of east Asia." As part of the national revival they hoped to foster, they embraced Western sports to counter the Mandarin paradigm of Chinese men as spindly, sedentary and effete.

Despite the reformers' efforts, to some degree the old paradigm has remained alive. Traditionally, most Chinese have been brought up to think they should be clever, disciplined and able to bear hardship, but not powerful or swift. Because Yao Ming's jousts with fellow NBA giants and Liu Xiang's triumph in the 110-meter hurdles at the 2004 Athens Olympics shattered racial stereotypes, they were hailed as breakthroughs by a new generation of Chinese. The 2008 Beijing Olympics, where China hopes to win more medals than any other nation, also was intended to have a political message.

Since abandoning doctrinaire socialism three decades ago, China has enjoyed an economic explosion that has given its 1.3 billion people a standard of living their parents could hardly imagine, and the government has entered into normal relations with most countries, becoming a diplomatic as well as an economic player in Asia and beyond. By hosting the Games, China was going to celebrate this status. Perhaps more important, it was going to receive international recognition of its achievements and, in some measure, acceptance of the Communist Party's glacial pace toward political change.

Xu's misfortune, and China's, is that this landscape, which he ably paints in his final chapter, shifted not long after the manuscript was sent to the printer. Riots in Tibet and protests along the Olympic Torch relay route created a global audience for questions about China's worthiness to host the Olympics. The atmosphere has soured badly, and no one knows whether it can be repaired before the Games begin in August.

The May 12 earthquake in Sichuan also will affect the Olympics. A country in mourning, China is likely to attract sympathy. But sorrow may change the tone of the event. Xu's history of China's participation in the Olympics remains enlightening, but the unsettled 2008 Games have become the stuff of journalism, changing every day.

目录信息

1. Strengthening the Nation with Warlike Spirit

2. Reimagining China through International Sports

3. Modern Sports and Nationalism in China

4. The Two-China Question

5. The Sport of Ping-Pong Diplomacy

6. The Montreal Games: Politics Challenge the Olympic Ideal

7. China Awakens: The Post-Mao Era

8. Beijing 2008

Conclusion

· · · · · · (收起)

读后感

2008年,我还是一个初中刚毕业的小屁孩。那年的夏天,因为北京奥运会的举办而特别了起来。开幕式前的那些日子,电视台每天都会滚动播放有关奥运的节目,其中印象深刻的有92巴萨罗那奥运点火是用弓箭射向火炬台点燃的。而且因为初二的时候喜欢上了篮球,在这个暑假还在小本子上...

评分2008年,我还是一个初中刚毕业的小屁孩。那年的夏天,因为北京奥运会的举办而特别了起来。开幕式前的那些日子,电视台每天都会滚动播放有关奥运的节目,其中印象深刻的有92巴萨罗那奥运点火是用弓箭射向火炬台点燃的。而且因为初二的时候喜欢上了篮球,在这个暑假还在小本子上...

评分2008年,我还是一个初中刚毕业的小屁孩。那年的夏天,因为北京奥运会的举办而特别了起来。开幕式前的那些日子,电视台每天都会滚动播放有关奥运的节目,其中印象深刻的有92巴萨罗那奥运点火是用弓箭射向火炬台点燃的。而且因为初二的时候喜欢上了篮球,在这个暑假还在小本子上...

评分徐国琦毕业于哈佛大学历史系,现任教于香港大学历史系,擅长国际关系史尤其中美关系史的研究。今年早前“理想国”引进了他的《中国人与美国人》,探讨晚清迄今的中美文化交流历史,全书分三部分,其中第三部分是“由体育运动而产生的共有外交旅程”,点出了体育与外交的微妙关...

评分徐国琦毕业于哈佛大学历史系,现任教于香港大学历史系,擅长国际关系史尤其中美关系史的研究。今年早前“理想国”引进了他的《中国人与美国人》,探讨晚清迄今的中美文化交流历史,全书分三部分,其中第三部分是“由体育运动而产生的共有外交旅程”,点出了体育与外交的微妙关...

用户评价

从翻开《Olympic Dreams》的第一页起,我就被卷入了一种难以言喻的情绪洪流之中。我并非一个狂热的体育爱好者,对奥运会赛场上的那些激动人心的时刻,我更多的是作为一名旁观者。然而,这本书却以一种极其深刻且富有感染力的方式,将我带入了一个全新的视角。作者以一种近乎历史学家的严谨,又带着诗人的敏感,描绘了那些“奥林匹克梦想”是如何被孕育、如何被锻造,又如何在那一次次的挑战与磨砺中,逐渐显露光芒。我仿佛看到了那些在黎明前就已经开始训练的身影,听到了他们在突破极限时咬牙切齿的喘息,感受到了他们在遭遇挫折时的心痛。这本书并没有回避梦想背后的艰辛与代价,相反,它将这些毫不掩饰地展现在读者面前,让我们得以窥见那些站在领奖台上的身影,背后所付出的难以想象的努力。我特别喜欢书中对个体奋斗历程的细致刻画,那些微小的进步,那些看似平凡的坚持,在作者的笔下却被赋予了非凡的意义。它让我重新审视了“成功”的定义,它并非偶然,而是无数次坚持与牺牲的必然。

评分当我拿起《Olympic Dreams》时,我并没有预设它会给我带来如此深刻的震撼。我并非一个狂热的体育爱好者,对那些赛场上的辉煌,我更多的是作为一名旁观者。然而,这本书却以一种极其深刻且富有感染力的方式,将我带入了一个全新的视角。作者以一种近乎历史学家的严谨,又带着诗人的敏感,描绘了那些“奥林匹克梦想”是如何被孕育、如何被锻造,又如何在那一次次的挑战与磨砺中,逐渐显露光芒。我仿佛看到了那些在黎明前就已经开始训练的身影,听到了他们在突破极限时咬牙切齿的喘息,感受到了他们在遭遇挫折时的心痛。这本书并没有回避梦想背后的艰辛与代价,相反,它将这些毫不掩饰地展现在读者面前,让我们得以窥见那些站在领奖台上的身影,背后所付出的难以想象的努力。我特别喜欢书中对个体奋斗历程的细致刻画,那些微小的进步,那些看似平凡的坚持,在作者的笔下却被赋予了非凡的意义。它让我重新审视了“成功”的定义,它并非偶然,而是无数次坚持与牺牲的必然。

评分这本书的叙事方式,就像一股清泉,缓缓流淌,最终汇聚成一股强大的力量,冲击着我的心灵。我一直认为,伟大的作品,不应该仅仅停留在表面,而应该能够深入到人性的肌理之中,展现那些最真实、最动人的情感。而《Olympic Dreams》正是这样一本,它用一种极其细腻且富有力量的笔触,描绘了那些“奥林匹克梦想”是如何在无数个平凡的日子里,被一点点地孕育、被一次次地考验,最终绽放出耀眼的光芒。我被那些关于坚持、关于付出、关于自我超越的故事深深吸引。作者的文字,如同一位温厚的长者,用他深刻的洞察力,引导我看到了那些运动员们在面对孤独、面对伤病、面对自我怀疑时的脆弱与坚韧。我读到他们如何在无数个漫长的黑夜里,独自与梦想搏斗,如何在高强度的磨砺中,依然保持着对未来的希望。我尤其欣赏作者对细节的捕捉,那些微不足道的瞬间,在作者的笔下却被赋予了生命,它们不仅仅是故事的组成部分,更是人物内心世界的写照。这本书让我明白,所谓的“奥林匹克精神”,不仅仅是赛场上的荣耀,更是人生中面对困难时永不放弃的勇气。

评分这本书给我带来的,是一种久违的、被文字深深触动的感动。我一直认为,真正的力量,并非来自声嘶力竭的呐喊,而是来自内心的坚守与不懈的追求。而《Olympic Dreams》正是这样一本,它用一种极其沉静而又充满力量的叙事,将我引向了那些不为人知的角落,让我看到了“奥林匹克梦想”是如何在平凡的生活中,一点点地被孕育和滋长。我被那些关于坚持、关于付出、关于自我超越的故事深深吸引。作者的文字,如同一面镜子,映照出那些运动员们在面对孤独、面对伤病、面对自我怀疑时的脆弱与坚韧。我读到他们如何在无数个平凡的日子里,重复着枯燥的训练,如何在高强度的压力下,依然保持着对梦想的执着。我尤其欣赏作者对人物内心世界的细腻刻画,那些不为人知的挣扎,那些对于未来的憧憬与迷茫,都让这些人物变得更加立体和真实。这本书让我明白,真正的伟大,往往就蕴藏在那些不为人知的坚持和付出之中,它不仅仅关于体育,更关于人生。

评分当我捧起《Olympic Dreams》这本书时,我并没有预设它会给我带来如此深刻的震撼。我一直认为,体育赛事,尤其是奥运会,是遥不可及的,是属于那些天赋异禀、体魄强壮的少数人的。但这本书,却以一种出人意料的方式,将我拉近了距离,让我看到了那些光鲜背后的真实。我被那些关于梦想如何被塑造,如何被捍卫的叙述所打动。作者并没有刻意去歌颂胜利,而是将更多的笔墨放在了那些为了胜利而付出的艰辛过程。我读到了运动员们在面对伤病时的痛苦与无奈,读到了他们在遭遇挫折时的绝望与不甘,读到了他们在自我怀疑的泥沼中苦苦挣扎的场景。这些真实而鲜活的描写,让我对这些“奥林匹克梦想”的追求者们,生出了一种由衷的敬意。我特别欣赏作者对时间和空间的运用,他能够将不同时间、不同地点的故事巧妙地串联起来,形成一种宏大的叙事图景。这本书让我明白,成功并非偶然,而是无数次坚持和付出的必然结果。它不仅仅是一本关于体育的书,更是一本关于人生智慧的书,它教会了我如何面对挑战,如何坚持梦想,如何超越自我。

评分这本书给我带来的感受,就像是在一片广袤的黑暗中,突然出现了一束明亮而温暖的光。我并不是一个天生的读者,对那些需要高度专注和理解的书籍,我常常会感到一种难以逾越的障碍。然而,《Olympic Dreams》却以一种极其流畅和引人入胜的方式,将我带入了一个充满生命力的世界。我被那些文字深深吸引,它们不仅仅是在讲述故事,更是在描绘一种生活,一种态度,一种对极致的追求。我仿佛看到了那些运动员在无数个清晨,顶着寒风,在空旷的训练场上奔跑的身影;我仿佛听到了他们在每一次突破极限时,咬牙切齿的喘息声;我仿佛感受到了他们在每一次比赛失利后,独自舔舐伤口的孤独。作者的叙事技巧非常高明,他能够将宏大的主题,细化到每一个微小的细节,让读者在感受故事的同时,也能从中汲取力量。我特别欣赏他对人物内心世界的刻画,那些不为人知的挣扎,那些对于荣誉的渴望,那些对于梦想的执着,都让这些人物变得鲜活而立体。这本书不仅仅是关于体育,它更是一部关于人生、关于梦想、关于坚持的赞歌。它让我明白,无论我们的梦想是什么,只要我们愿意付出,愿意坚持,我们都有可能实现它。

评分这本书的封面上,那一抹金色的光芒似乎就在预示着某种极致的追求,当我在书店偶然翻开它时,一种难以言喻的冲动便攫住了我。我是一个对运动,尤其是奥运会有着深深迷恋的普通人,那些赛场上的瞬间,不仅仅是汗水与泪水的交织,更是人类精神最纯粹的体现。我一直渴望能够深入了解那些站在最高领奖台上的运动员背后,究竟隐藏着怎样的故事,怎样的付出,怎样的挣扎。这本书,就像一把钥匙,轻轻一转,便为我打开了一个全新的视角。它并没有直接描绘赛场上的激烈角逐,而是将我引向了那些不为人知的幕后,那些在无数个平凡的日子里,无数次重复的训练,无数次与伤病的搏斗,无数次在自我怀疑的深渊中挣扎的画面。我仿佛能听到每一次心跳的回响,感受到每一次肌肉撕裂的疼痛,甚至能嗅到训练馆里那混合着汗水、器材和一种难以名状的决心的气息。作者以一种近乎诗意的笔触,描绘了这些“奥林匹克梦想”的孕育过程,它并非一蹴而就,而是由无数微小的火星汇聚而成,最终点燃了燎原的火焰。我特别欣赏作者对细节的捕捉,那些看似微不足道的动作,在作者的笔下却被赋予了生命,它们不仅仅是训练的组成部分,更是运动员内心世界的写照。这本书让我重新审视了“伟大”的定义,它并非只属于胜利者,而属于每一个在追求梦想的道路上,从未放弃过自己的人。

评分我一直认为,阅读的魅力在于它能够将我带入一个全新的世界,而《Olympic Dreams》无疑做到了这一点,而且是以一种极其震撼的方式。我并不是一个运动员,也从未体验过那种日复一日、年复一年的高强度训练,但这本书却让我身临其境,仿佛我就是那个在黎明破晓前就已经开始挥汗如雨的年轻人,那个在深夜独自面对镜子,审视自己不足的运动员。作者的文字充满力量,但又不过分煽情,他用一种冷静而深刻的观察,揭示了梦想背后隐藏的巨大代价。我读到那些为了梦想而放弃的社交生活,那些因为训练而不得不与家人朋友疏远的时刻,那些在关键时刻因为一点点失误而与胜利失之交臂的痛苦。这本书并没有回避这些残酷的现实,相反,它将它们赤裸裸地展现在读者面前,让我们得以窥见“奥林匹克精神”的真正含义——它不仅仅是拼搏,更是牺牲,是坚韧,是面对失败时依然能够重新站起来的勇气。我特别喜欢书中对于运动员心理描写的那些段落,那些内心的独白,那些对于胜负的焦虑,对于未来的迷茫,都让我感同身受。这本书让我明白了,即使是最耀眼的明星,他们也曾经是普通人,也曾经有过恐惧和不安,正是因为他们能够克服这些,才最终成就了他们的辉煌。

评分我一直对那些能够将宏大的主题,以一种极其个人化、极其细腻的方式呈现出来的作品,有着天然的好感,而《Olympic Dreams》无疑是这样的一本书。我并不是一个热衷于体育的人,对于那些赛场上的辉煌,我总是隔着一层若有若无的距离。然而,这本书却以一种出人意料的方式,拉近了我与那些“奥林匹克梦想”之间的距离。我被那些关于坚持、关于付出、关于自我超越的叙述深深吸引。作者并没有刻意去渲染赛场上的残酷竞争,而是将更多的笔墨放在了那些在幕后默默付出的个体身上。我读到了他们面对伤病的痛苦,读到了他们在遭遇挫折时的绝望,读到了他们在自我怀疑的深渊中苦苦挣扎的场景。这些真实而鲜活的描写,让我对这些追逐梦想的人们,生出了一种由衷的敬意。我尤其欣赏作者对人物心理的描绘,那些内心的独白,那些对于未来的憧憬与迷茫,都让这些人物变得更加立体和真实。这本书让我明白,所谓的“奥林匹克精神”,不仅仅是赛场上的拼搏,更是人生中面对困难时永不放弃的勇气。

评分我一直对那些能够将平凡的生命故事讲述得跌宕起伏,感人至深的作品情有独钟,而《Olympic Dreams》恰恰是这样的一本书。它并非以惊险刺激的情节取胜,而是以其细腻入微的情感描写,以及对人性深处挖掘的深度,深深地吸引了我。当我开始阅读这本书时,我并没有抱有多大的期望,我只是一个普通的读者,对于那些宏大的叙事,我常常会感到一种疏离感。然而,作者的文字却以一种不可思议的魔力,将我带入了一个充满激情与奋斗的世界。我仿佛能够看到那些运动员在训练场上挥洒的汗水,听到他们在赛场上呐喊的声音,感受到他们在面对挑战时内心的起伏。我被那些关于梦想如何被一点点孕育,如何被一次次考验的叙述所打动。我尤其欣赏作者对细节的关注,那些微不足道的瞬间,在作者的笔下却被赋予了生命,它们不仅仅是故事的组成部分,更是人物内心世界的写照。这本书让我明白,真正的伟大,往往蕴藏在那些不为人知的坚持和付出之中。它不仅仅是一本关于体育的书,更是一本关于人生选择和价值追求的书。

评分读了前两章,介绍了“体育”在近代中国的兴起和中国的奥运政治,史实为主,不过也没有特别多的细节,线条比较粗

评分读了前两章,介绍了“体育”在近代中国的兴起和中国的奥运政治,史实为主,不过也没有特别多的细节,线条比较粗

评分粗略翻了翻,感觉内容比较简单基本成为体育大事件回顾编年史。argument也有新瓶装旧酒之嫌。截止到08奥运颇有“蹭热度”感觉。

评分读了前两章,介绍了“体育”在近代中国的兴起和中国的奥运政治,史实为主,不过也没有特别多的细节,线条比较粗

评分读了前两章,介绍了“体育”在近代中国的兴起和中国的奥运政治,史实为主,不过也没有特别多的细节,线条比较粗

相关图书

本站所有内容均为互联网搜索引擎提供的公开搜索信息,本站不存储任何数据与内容,任何内容与数据均与本站无关,如有需要请联系相关搜索引擎包括但不限于百度,google,bing,sogou 等

© 2026 book.wenda123.org All Rights Reserved. 图书目录大全 版权所有